A Secret Weapon

by Laurel Schlegel

Cpl. Henry Bake, Jr., and Pfc. George H. Kirk, Navajo Indians serving with a Marine Corps signal unit, December 1943. (National Archives and Records Administration)

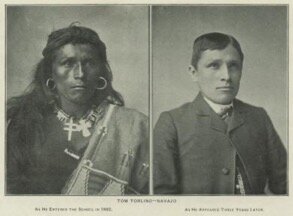

Tom Torlino, a member of the Navajo Nation, as he appeared upon arriving at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1882 (left); the photo on the right was taken three years later. Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle School, hired photographers to take images of native students before and after their time at Carlisle, with the intention of highlighting the ways in which the school “civilized” members of its student body. Boarding schools like Carlisle, and the institutions attended by veterans John Werito and Edward Leuppe, attempted to assimilate native peoples into the mainstream “American” way of life. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Boy’s dormitory of the Southern Ute Indian Boarding School, 1942. John Werito attended the school prior to serving as a Navajo Code Talker in World War II. (Library of Congress)

Navajo Code Talker John Werito

May 2, 1923-March 29, 1983

Marine veteran and Navajo Code Talker, John Werito, is an important figure in both Native American history and American history more broadly. He was born in Star Lake, New Mexico on May 2, 1923.[1] He grew up on a reservation before being sent to the Indian Southern Ute Boarding School in Ignacio, La Plata, Colorado.

Indian Boarding Schools, like the one that Werito attended, removed Native American children from their homes and families in an attempt to re-educate students and assimilate them into American society.[2] At these boarding schools, Native American children were punished for speaking their native tongue. If students did not speak in English, teachers could inflict corporal punishment.[3] Ironically, it was at these boarding schools—where Indian children were forbidden from speaking their native language—that the U.S. Army recruited young men to use their indigenous language in the battlefield, fighting for the very country that attempted to destroy their culture.

After graduating from the boarding school in the summer of 1942, Werito was drafted into the Marines on April 26, 1943, at age 19.[4] He was first sent to the Camp Pendleton Marine Corps Base in California, where he was trained as a Navajo Code Talker and radioman.[5] The Navajo Code Talkers transmitted and decoded messages during World War II in order to conceal the movements and plans of the U.S. military from the enemy. At Camp Pendleton, Code Talkers completed extensive training in communication and had to not only learn the code, but memorize it as well.[6] Prior to Navajo involvement, code machines were used to translate messages and the process could take up to thirty minutes. Navajos could translate the code in just seconds.[7]

The use of Native American language as code did not originate in World War II, however. During World War I, a group of Choctaw men in the 36th Infantry Division began using their language as a military code. It was the first code that the Germans were unable to break, and gave the Allied Forces a huge advantage. Within three days of using the Choctaw language, which was not Latin based and was unable to be interpreted by the enemy, the German forces were in full retreat.[8] These brave soldiers paved the way for the Navajo Code Talkers to have as much impact as they did.

After completing training at Camp Pendleton, Werito was assigned to the Fourth Marine Division in Maui, Hawaii.[9] He first saw action in the Pacific Theater when his unit was sent to the Asian Pacific Islands Roi and Namur.[10] Roi and Namur were the first of the Marshall Islands to be captured by U.S. troops, which would allow an advance into the Philippines and Japanese home lands. The United States greatly outnumbered the Japanese, but Japan fought until the end, with fewer than 200 Marines dying in both assaults.[11] Werito’s unit was then sent to the island of Saipan. The assault on Saipan began on June 15, 1944 and lasted until July 9th. The fighting was especially brutal on this island given its mountainous terrain.[12] During this battle Werito sustained minor wounds, but after a quick recovery he participated in the invasion of Iwo Jima beginning in February of 1945.[13] Unfortunately, while in combat, he was wounded for a second time, this time more severely.[14] However, during just the first two days on the island, the Code Talkers successfully transmitted over 800 messages. The Japanese never broke the code.[15] Major Howard Connor, a Marine Signal Officer, claimed that, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”[16]

On November 28, 1945 Werito received an honorable discharge from the Marines as a Private First Class at the U.S. Naval Base in Mare Island, California.[17] The Navajo Code Talkers had a huge impact in World War II, especially in the Pacific. Through the use of their native language as a complex code they could send messages unbreakable by the Japanese. The code talkers were a secret weapon that proved instrumental in the United States success in the Pacific theater.

After his discharge, Werito returned to Colorado and settled in Denver.[18] Upon recovering from his injuries, he reenlisted in the Marines and remained in the active Marine Corps Forces Reserve in Colorado.[19] It was during this time that he married Rose Marie.[20] In May of 1951 he was preparing to ship out to Korea as a Code Talker, when his daughter Nellie was born. He was allowed a discharge and got a job as a United States Postal Service carrier.[21] He and his wife later had a second child, Michael J. Werito.[22] They moved several times around the Denver area. Werito eventually retired in 1973;[23] he died on March 29, 1983, and was buried at Fort Logan National Cemetery.[24] On November 24, 2002 his wife attended a ceremony in which John Werito, along with his fellow Navajo Code Talkers, were awarded a Congressional Silver Medal of Honor.[25] Werito’s story of bravery and service is one of not only a Navajo Code Talker, but an American Indian as well. Native Americans have volunteered for war at a rate twice that of the rest of the American population since the First World War, and their service deserves to be remembered.[26] After the work of Werito and his fellow code talkers in World War II, the Navajo language and culture, which U.S. federal and religious officials once sought to destroy, would become appreciated instead of ridiculed.