American at Heart

By Mathew Greenlee

Albert S. Akiyama

August 9, 1910-June 15, 2010

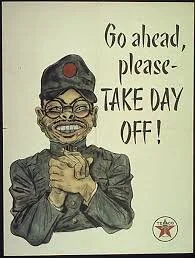

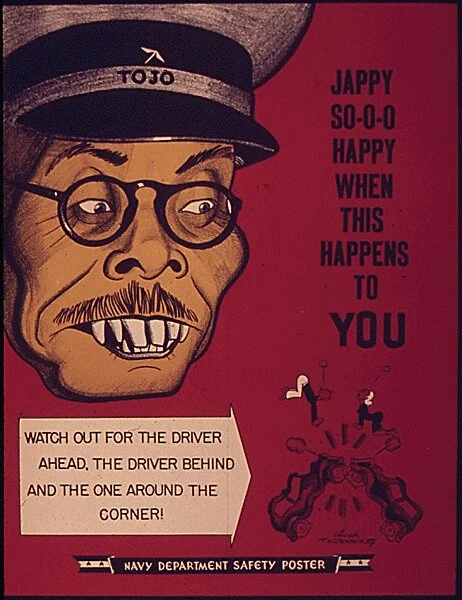

Albert “Bert” Akiyama was born August 9, 1910 in Santa Clara, California into a family with four other siblings.[1] By his tenth birthday, Albert’s father passed away.[2] Bert grew up on a fruit farm outside of Redwood City where he worked until his late twenties.[3] In his thirties, he became a janitor.[4] Albert was one of many Nisei (second generation) Japanese Americans growing up on the West Coast at the time. As relations between Japan and the United States slowly soured, relations between white Americans and Japanese Americans, which had been tense for decades, began to deteriorate. As the United States government prepared for war, it prepped its populace for war against the Japanese by releasing various propaganda posters convincing America of the backwardness of Japan, which capitalized on the underlying racial animosity that had already existed. This propaganda permeated through every facet of American life.

Bert would see the nation slowly turn to hatred. Three months after Pearl Harbor and the United States entrance into the war, on January 22, 1942, Bert decided to enlist in the military and fight against the Germans, Italians, and Japanese.[5] One must wonder about such a decision. During this period of hatred for the Japanese, a man born and raised in an immigrant Japanese family, while being a US citizen himself, decided that it was in his best interest to fight for the country that seemed to view him as an enemy. Many Japanese Americans went on to fight for the United States because they believed they had to prove to Americans that they were just as worthy of citizenship as their white counterparts. Some enlisted for money, and some enlisted as an opportunity to give back to the nation they had come to call home. The specific reasons why Bert enlisted remain unknown.

Few Japanese Americans would have been able to predict what happened 27 days after Bert’s enlistment. On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.[6] This called for the “relocation” (incarceration) of all Japanese and Japanese Americans in the continental United States. Earlier that year, on January 5, the War Department had classified all Japanese Americans as 4-C, ineligible for military service and subjugated as “enemy aliens.” Despite this, a few hundred Nisei were still able to enlist and Bert himself was not relocated because of his having already enlisted in the military. After five months of what was undoubtedly unprecedented bureaucratic shuffling and confusion, Bert was sent to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin where the 100th Infantry Battalion was to be trained for service. By January of 1943, impressed by the outstanding performance in training by the 100th Battalion, the War Department announced plans to organize an all-Japanese American combat unit, which would become the 442nd. Of 1,500 requested Japanese-Americans from Hawaii, where there were no internment camps, almost 10,000 volunteered, whereas on the continental US, 1,200 volunteered. Most of these volunteers came from internment camps.[7] In Hawaii, the majority, though not all, of the Japanese American population were not placed in internment camps. Instead, martial law was announced, and their movements and freedoms were strictly limited.[8]

President Harry Truman inspects the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team on July 15, 1946. [16]

After months of intense training, the 100th and 442nd were sent to Europe to their first opportunity at combat. Bert was a Sergeant and part of I Company, 3rd Battalion.[9] The 442nd would go on in the months that followed to become the most decorated military unit in American history.[10] The unit was known for extreme capability, and commitment to its cause. Due to the casualties it sustained throughout the war, of its 3,800 members it had a replacement rate of 324%, would go on to receive 7 Presidential Unit Citations, and in total the soldiers in the regiment would receive 9,486 Purple Hearts.[11] Bert would be released with a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart, and a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster. Much of the regiment’s fame would come from its rescue of the “Lost Battalion”, during which the 442nd would lose almost 800 of its men to save 211 men of the 141st Infantry. Their actions, including especially the actions of I and K Company in the 3rd Battalion, of which Bert was now a Staff Sergeant, were incredible to recount.[12]

After the end of the war, tensions between races in the states were still high. However, the actions of the 100th and 442nd gave force to the argument that Japanese Americans were indeed fully worthy of being respected and viewed as full citizens. Bert would be released from the military at age 36. He would move to Aurora, Colorado where remembrance remained an active part of his life. He participated in the writing of at least three books,[13] all based on his experience in WWII with the 442nd, and even donated to the creation of a memorial for Nisei soldiers in Fairmount Cemetery in Denver, CO.[14] He would go on to have three children and die at the age of 99.[15] The actions of Bert and the 442nd proved to the United States that Roosevelt, the man who interned thousands of Japanese Americans, was right. That being American is not a matter of race or creed, but of heart.

![President Harry Truman inspects the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team on July 15, 1946. [16]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cdee20d61310c0001c2cbbe/1605070876328-Q6IQMKOPILG0HJNC1IQF/image-placeholder-title.jpg)